Earlier this month, we posted a photo on social media following Laura Kraut and the 11-year-old Zangersheide mare Bisquetta’s victory in the Rolex Grand Prix of Dublin.

Second-last to go on course designer Alan Wade’s challenging, 1.60m grass track, Kraut and Bisquetta were the only clear of the day on a course that saw more than a dozen horses retire. But it was Kraut’s post-class quote, shared along with a photo, we posted on Facebook that garnered the most attention.

In the post, Kraut describes Bisquetta as being “terrified of other horses” specifically when they “swish their tails.” She notes that, while Bisquetta is “very sweet” and does her job in the ring, she “just doesn’t like people around her, doesn’t like other horses.”

More than 445 people weighed-in in the comments section about Kraut’s sentiments and the accompanying photo.

For the purposes of this story, we wanted to delve into Kraut’s comments, and reached out to our go-to expert, equine behavior specialist Renate Larssen, for insight. Larssen has a Bachelor of Science degree in Veterinary Medicine from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and a Master of Science degree in Ethology (the study of animal behavior) from Linköping University in Sweden. She’s currently working on her PhD.

HN: It’s hard to determine from Kraut’s comments in what context she’s talking about Bisquetta’s “quirks” as they relate to her feelings about other horses: whether this is in all cases, in the warm-up ring, in the field, when she encounters them in the barn aisle, etc. Taking that aside, if we assume that horses, like people, are individuals, with individual preferences and traits, how do we, as their caretakers, determine what’s a preference/character trait, and what’s a stress reaction?

RL: How we talk about behavior is important. The reason behavior matters to us is because it tells us something about the emotional experience of the animal. The danger with using anthropomorphizing words such as “quirky” to describe behavior is that these words don’t tell us anything about the meaning of the behavior, i.e. the horse’s experience in the moment. When we see behaviors that indicate that a horse is having a negative experience, such as escape and avoidance behaviors, we need to take them seriously regardless of the personality of the horse.

I think it’s worth briefly defining the three components personality, preference and stress here. Personality designates behavioral responses that are consistent over time. Preference is what an animal likes or dislikes. Stress is a physiological response to any situation that requires some type of action on the part of the animal, and which has an emotional component.

These three components interact in complex ways to create behavioral responses to specific situations. Preferences determine whether a horse will find a particular situation pleasant or unpleasant—unpleasant situations cause stress and negative emotions, and personality traits determine how the horse responds to these negative emotions. I am simplifying this for clarity, but it is important to remember that, in reality, behavior is very complex and influenced by many additional internal and external factors.

HN: One recurring sentiment in the comments of this post is that horses are herd animals, and that if Bisquetta “doesn’t like other horses,” she’s not behaving normally, and is therefore under stress. I’m curious as to your thoughts on that, and also the nature of horse social behavior. If Kraut was talking about a specific situation like a warm-up ring, is it reasonable to assume there is a difference between how a horse reacts to strange/unknown horses in her surroundings vs. horses in her “herd” or social group, such as a turnout situation at home?

RL: To understand Bisquetta’s behavior, we need to first consider the social lives of horses. Horses have a deeply rooted need for the company of other horses, and while we humans increasingly acknowledge this, it is still often misconstrued as “any horse will do.” However, the preferred social structure for horses is to live in close-knit, stable groups based on family ties.

Within these groups, horses will associate preferentially with certain individuals and not others, meaning they choose who they want to be friends with. Several groups will share a home range, and they will acknowledge and interact with each other, while at the same time maintaining the cohesion and integrity of their own chosen group. Some horses will switch groups repeatedly, while others may stay in the group they were born into all their life.

This complex social network is negotiated and maintained through highly attuned social interactions. When two unfamiliar horses meet, they interact with each other according to the rules of equine social etiquette: they approach each other mindfully and communicate their identity and intent through body language and facial expressions.

The purpose of this subtle communication is to avoid conflicts, similar to our human social rules that dictate how we interact with strangers in public spaces. It is considered impolite for us to walk straight up to someone we don’t know, stand very close to them and yell in their face. Something similar can be said about horses.

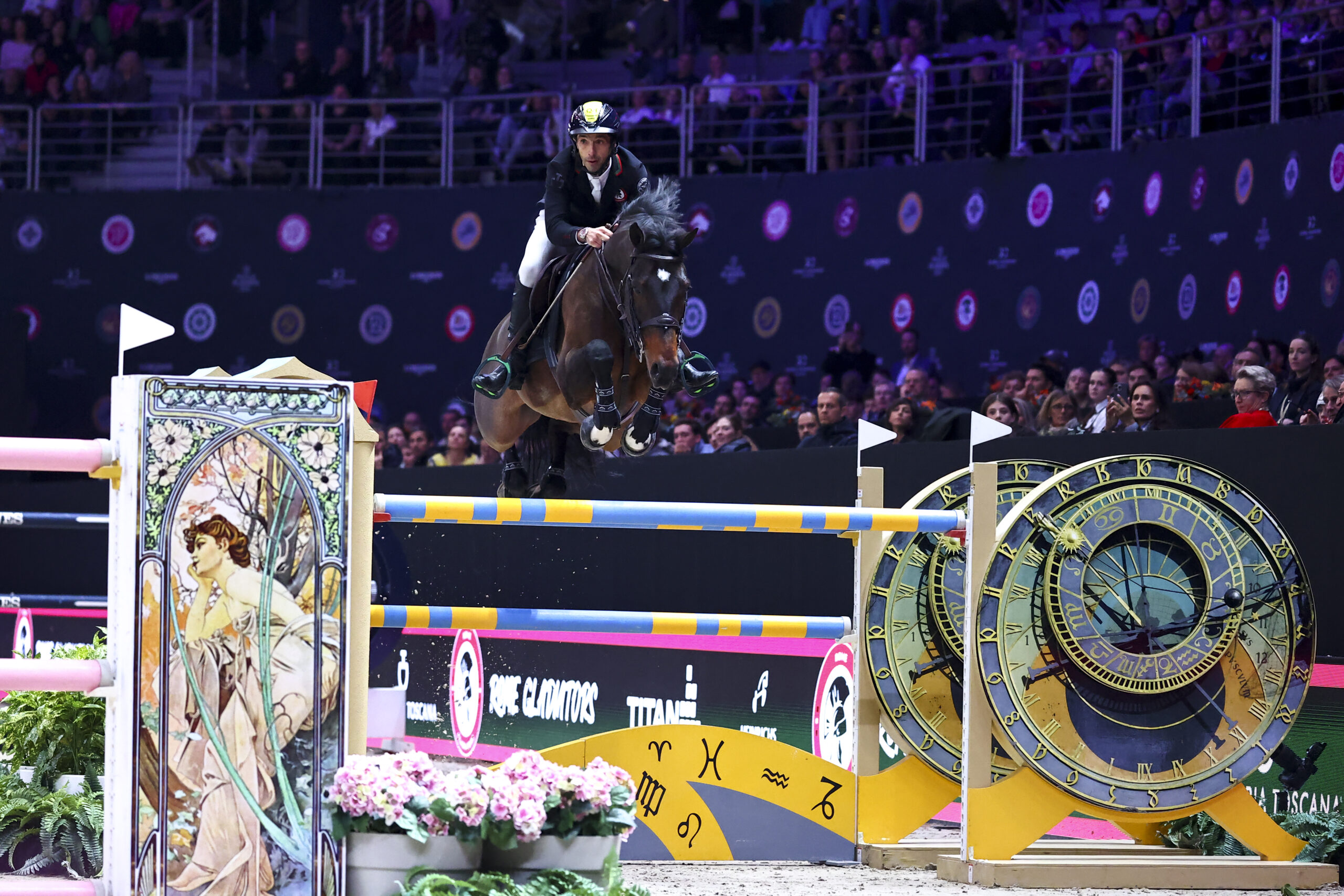

So, when two unfamiliar horses meet in a confined space, their social rules dictate that they approach each other slowly, in a curved line, and indicate through body language (for example by looking away and lowering their heads) that they don’t have hostile intentions. But ridden horses aren’t allowed to engage in such polite exchanges with each other.

Instead, we ask them to simply keep moving in a straight line, sometimes running at speed directly towards the other horse, and fixate their head with the reins so they can’t communicate friendly intentions. This forces them into an unnatural social situation that can be very stressful, because the cost of not following social etiquette in the equine world—essentially behaving “rudely”—is physical confrontation, i.e. getting bitten or kicked.

This is why it can take time for young horses to get used to “ignoring” other horses in an arena, for example, and why some horses react fearfully or aggressively to other horses coming near them. It’s a natural response to an unnatural social situation, and it can be exacerbated by a previous bad experience.

I found it interesting that Kraut specifically mentions that Bisquetta is afraid of tail swishing, as that is a classic behavior associated with aggression, and an early warning sign of an impending kick. Perhaps Bisquetta has previously been at the receiving end of a kick and is now highly attuned to subtle signals to avoid finding herself in a similar situation again?

It is also important to remember that stress is not all-or-nothing. Rather, it compounds, and many small stressors will add up over the course of the day, week, or month. So, a horse that may cope well enough with other horses in the arena at home might not be able to do so away at a competition, in an unfamiliar environment, with changed routines and new sounds and smells.

While horses can have preferences as to which horses they like or don’t like, just like we have preferences as to who our friends are, it is not normal for horses to respond with fear or aggression towards all horses at all times. This is a clear indication that something is wrong.

It could be that the horse has been poorly socialized in their youth and therefore lacks vital social skills, that they have had a traumatic experience in the past that makes them wary of other horses, that they are in pain, or that there is insufficient space for them to be able to achieve a comfortable interaction. It could also be a combination of factors. Either way, a horse that is unable to live with other horses should be given help and support to learn how to socialize in a healthy and safe way through professional behavioral rehabilitation.

HN: When it comes learning how we can better prioritize our horses’ basic needs and welfare, is it reasonable to expect that all horses ‘without stress’ are going to fall within a narrow definition of behavioral norms? Are there peculiarities, like Kraut describes, that could be acceptable for some horses but not for others?

RL: I find “stress” an awkward concept in discussions of welfare, because it designates a physiological state of high arousal but says very little about the underlying emotional experience, which is what matters to us.

We want our horses to be mostly comfortable and content with their lives, and to only rarely experience fear and anger, and preferably never because of the things we do to them. A horse that displays escape or avoidance behaviors is doing so because they are afraid, and so, we should take these behaviors seriously regardless of their personality or competitive level.

With that said, the question of personality and individual abilities and preferences is an important one in this context. Some horses are more socially resilient, for example, and can cope better with social instability, unfamiliar horses, and novel situations (although the key word here is cope, not thrive; no horse can really thrive under these conditions). These horses might be more suited to life as competition horses than others, for example.

HN: Let’s use the example again of the horse who is having a stress response because it doesn’t like other horses, or something else, in a warm-up situation, even if it performs well alone in a show ring. Can you give us a sense where, in your view, the ethical line should fall in the decision-making for that horse?

RL: In my opinion, we are obliged to take our horses’ fears seriously and we should consider their experience during all parts of the competition, not just in the show ring. A horse that is showing behaviors indicative of stress, fear, or separation anxiety during transport, stabling, in the warm-up ring, or during the prize-giving ceremony is not fit to compete, regardless of their performance during the actual event.

Rather than writing off these behaviors as “quirks” we should acknowledge that our horses are struggling, and take on the responsibility of helping them cope. The good news is that a lot can be done through pedagogical and compassionate training (gradual exposure, positive reinforcement, etc.) and by making reasonable adjustments to the environment (warming up outside the warm-up arena, doing the prize-giving ceremony on foot, etc.).

Additionally, thinking about “the other 23 hours,” particularly in terms of minimizing other sources of stress, can be really helpful. Horses that have adequate access to the 3Fs [friends, forage, and freedom], who live in stable social groups, are healthy and not in pain, will be more resilient and better able to cope with the challenges of a competition environment.

HN: Anything else you would add?

RL: I just want to emphasize that horses behave in ways that are meaningful to them even if we don’t always understand why they are doing what they are doing. We should always regard their behavior seriously, because it tells us something about how they feel in a given situation.

Learn more about Renate Larssen at theequineethologist.substack.com

August 20, 2025

August 20, 2025