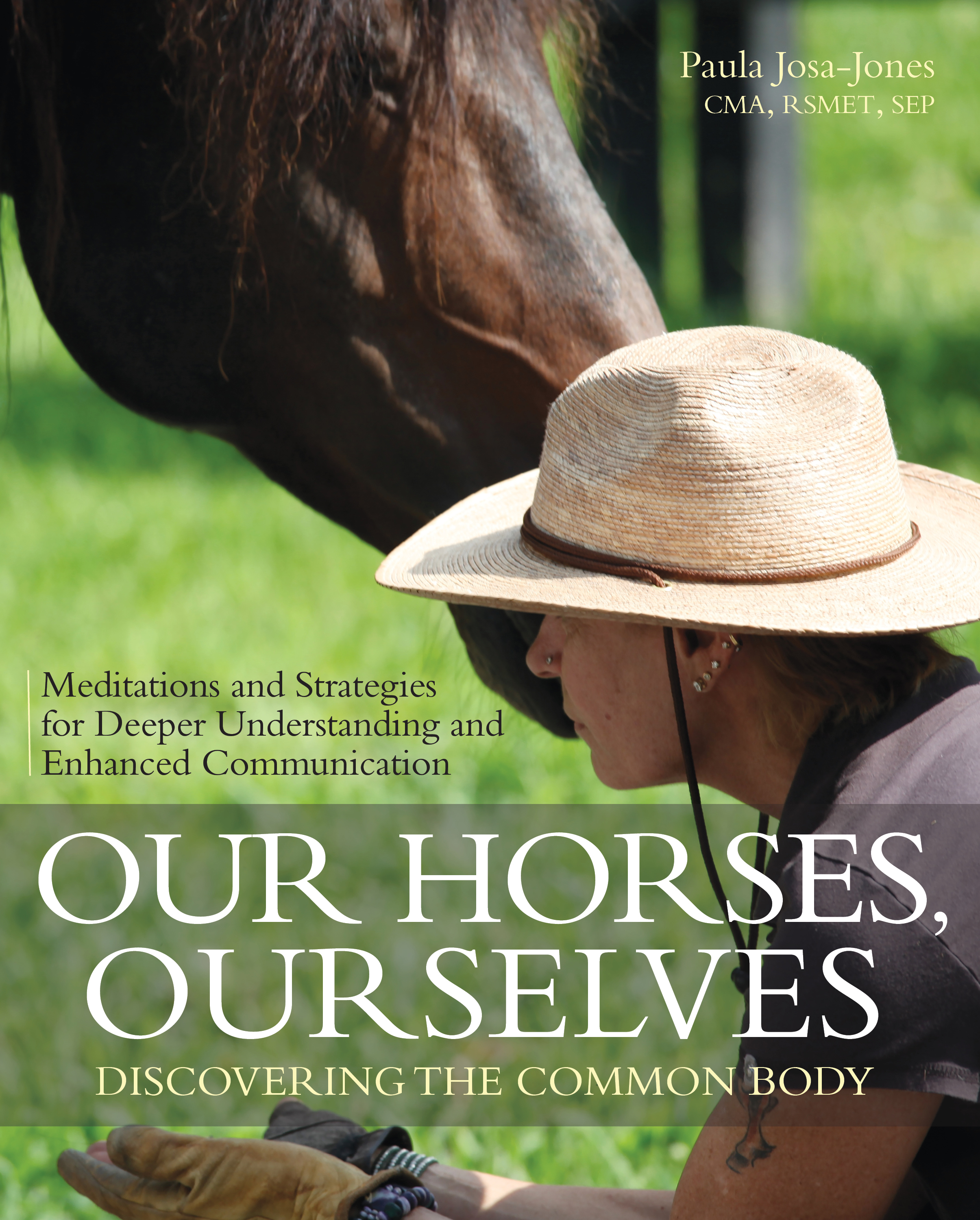

In her new book Our Horses, Ourselves: Discovering the Common Body, world-renowned dancer and choreographer Paula Josa-Jones explores how horses help what needs helping, and the role our bodies, their bodies, and movement play in our sometimes complex relationships with them.

***

Amadeo, my lovely, complicated Andalusian, is my riding partner and my teacher.

When we first met, my hips were failing, worn ragged from years of dancing. Riding had become difficult, and I needed to find a horse partner that was easier on my body than my wide Friesian, Goliath. Just outside of Madrid, I was introduced to Amadeo, a gleaming dark bay. I was able to sit all his gaits—walk, trot, and canter. He was a beautiful, extravagant mover—soft and open in his strides. I felt like I was riding a cloud.

But by the time Amadeo arrived in the United States, sitting on any horse was agonizing for me. I had two successive hip replacement surgeries, and it was nearly eighteen months before I could safely ride again. When finally cleared to mount a horse, my body was a foreign territory. The delicate proprioceptors surrounding my hip joints had been terribly disrupted by the surgeries, my joints replaced with titanium and porcelain. My body did not know where it was in space or motion.

Riding Amadeo I was tentative and fearful. He read me perfectly and knew that, “Go,” really meant, “Don’t,” or “Slow.” That became our agreement: I asked and he refused. To make matters worse, he was skittish and reactive, perfectly mirroring my newfound nervousness. I struggled with my failures as a rider and my frustrations with this beautiful, inaccessible horse. I had occasional good rides, but mostly it felt as if we were speaking two very different languages. Even as I became stronger and bolder, it seemed that our confused communications were hard-wired.

I felt my anxiety growing on the way to the barn. Our rides felt more like a bitter, old argument than a friendly conversation. I sensed him watching me, waiting. My mind skittered: “I’m not breathing, my mind is rushing, I’m not with him.” With each ride, my expectation grew for him to misbehave, stop, or buck, and of course, reading my mind and body perfectly, he did just that. He threw his haunches to the left, curled his neck, tightened his body, and began an exaggerated, stilted, Spanish walk, bucked, or drifted sideways or crowhopped.

The problem wasn’t that Amadeo was frustrating, but that I was frustrated.

I remembered the words of my first trainer, Tom Davis, “Your frustration has absolutely no place in your riding.” And yet there I was, a dozen years later, my riding stuck in the cul-de-sac of fear and reactivity. I was embarrassed by my own limitations and realized that it was not about making small changes in my riding habits, but about completely changing the nature and the ground of the conversation I was having with my horse. I decided to take a complete break from riding Amadeo. I had to catch my breath, unravel my frustration, and see if I could soften and open the gates to possibility again.

Photo by Pam White.

I began to work with him on the ground, longeing him in a big circle on a loose line. My hope was that it might be a way to open a new understanding in our fraught relationship. I wanted to appreciate more about the link between my movement cues and his responses, and to build a more “feeling,” body-focused conversation between us. Slowly I began to figure out certain cues, how to express them more clearly with my mind and movement, and to better understand what he was telling me with his responses.

I visited another farm where a trainer who was longeing a horse said to me, “I am waiting to feel his mind in my hands.” I immediately understood that she was talking about a bridge between the consciousness and behavior of the horse and the sensation and understanding of that in her own body.

My next time working with Amadeo was different. I could feel and see when I had him “in my hands” and when I didn’t. When I saw his eyes going toward the outside of the arena, looking out the big doors, I softly “sponged” (squeezing and releasing) the longe line with my hand, and thought, with me. His inside eye came back to me, and his ear turned in toward me. In that moment I felt that I was listening to him, and that he was also listening to me. I realized I didn’t want just his mind in my hands; I wanted to feel his whole body, his breathing, his connection to the ground, his focus—and even his distraction and reactivity—so that my whole body was a receptive sensor for his.

Focusing this way, I felt no fear.

Photo by Pam White.

One day a horse walked by the arena as we were working. Amadeo exploded, prancing and blowing like a stallion, all big muscle taut at the end of my line. Miraculously, I did not panic or react, but softly asked him to move forward, and focused on breathing and grounding my own body, repeating mentally, with me, with me. Within a few minutes, he was calm.

My friend, the sculptor and painter Peggy Kauffman, once said, “I never sold a horse, I just learned how to ride the horse I had.” When she said that, I’d thought, “Yes, but…” because I could not imagine riding Amadeo after so many months of not being able to ride him.

But now, as I thought about her words, I began to believe that it might be possible.

This excerpt from Our Horses, Ourselves: Discovering the Common Body was reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books.

September 25, 2017

September 25, 2017