So another December has rolled around.

And for Americans in all but the most southern tier of states, this means that the toughest time looms ahead for those with horses—December, January, February, until at least about mid March. Roughly 100 days of frozen ground, dark days, colder weather, difficult trailer travel, long winter coats and for many, deep snow.

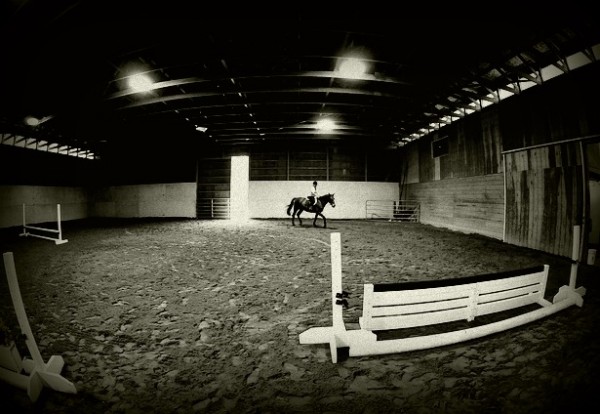

Some go south. Some have access to indoor riding. Some, the super diehards, tough it out in the open. I call these people “the kind that would ride by headlight, after work, in a North Dakota blizzard.”

Winter riding is not for the faint of heart but it doesn’t have to be “either/or,” and many riders and drivers and horse owners have developed coping mechanisms that are worth sharing.

© Tamarack Hill Farm

Winter Coping Strategy #1: Pull their shoes, turn them out, and say, “See you in March.”

This is what most people did when I was a kid, growing up in Greenfield, Mass, eight miles south of the Vermont state line, in the 1950s.

It was a different world 55-65 years ago. No indoor rings. The only one I remember was a dark little Quonset Hut type metal tube at Smith College. You rode outside, or you didn’t ride. The roads were narrow, twisty and snow covered. No Eisenhower Interstate System in those days, and almost nobody took horses south.

Some got their horses shod with borium so they would have traction on the ice, some pulled the shoes, and just figured, “Why fight the conditions?”

And, you know what? It basically didn’t hurt anything, as long as the horses got some sort of turnout for at least part of the day, and had access to plenty of water and plenty of hay. By March or April, they “got picked up” for spring, summer and fall riding, and, within a few weeks of slow work, were ready to go.

“Umm, what?” (youtube/Jessica Doersam)

No guilt, no great decline in skills, at least for the horses. (Now, if the humans had spent the winter in dark depression, eating much, exercising little, that was a different story…)

So if the prospect of endless frozen feet and hands is unappealing, and you want to bag it for a while, I think you can do so without having to feel like “a bad person.”

Winter Coping Strategy #2: If you decide to ride much of the winter and have access to an indoor arena…

Setting a specific goal is a great way to avoid the monotony of going around-and-around-and-around-and-around in endless circles, staring at the same walls, day after day.

(Modified from flickr.com/Serge Melki)

A good example of setting a definite, specific goal was something that Sue Berrill did 10-15 years ago. Sue is today one of the more accurate jumper riders around, but there was a time when her eye for a distance was more “shaky” than it is now.

Sue decided that she’d had “had it” with having rails down because of getting her horse too frequently to takeoff spots from which it had to struggle.

At the time, Sue was renting a farm in Windsor that had a fairly small indoor ring, and Sue said that she made a vow to herself:

“When I go into that indoor around Thanksgiving, I swear that by the time I get out of there by April, I WILL have a good eye.”

All winter, day after day, Sue “jumped” several horses over rails on the ground, and, within reason, actual jumping over small jumps, so that by spring Sue may not have become a Rodney Jenkins, but she had become a rider you can watch fence after fence and rarely see her miss.

That is one example of setting a definite goal and going after it heart and soul.

Winter Coping Strategy #3: Teaching conditioned response patterns, often at the walk.

First thing is to see if there is a time to ride indoors away from the frenzy of lots of action. Alone, or with one or two quiet riders is best. See if you can put on some music, get a low key atmosphere. Then teach the horse that a certain light pressure in direction “a” means give that way, in direction “b” the other way. This can be giving to hand pressure, or moving away from leg pressure.

Carolina Horse Park dressage, last January.

Pressure, compliance and release, light pressure—not “give me your head now” pressure—and putter along, walking as the horse gradually starts to understand that by giving to soft pressure from hand or leg, the pressure lessens or goes away. Always be vigilant about any nervousness. The horse needs to stay on an even keel and not feel undue anxiety. Back off, carefully “sneak” back, feel what’s going on.

Think of it as “stimulus-response.” I ask with a stimulus, say a light pressure on the left rein to the left. The horse responds by giving his head fractionally to the left. My response to his response is to lighten the stimulus that created the response in the first place.

Think of aids as non-verbal communications. I can’t say “Give to the left” in English, because he doesn’t speak English. My “words” are light pressures and softenings.

Gradually, the horse starts to “speak” the language of the aids. We are starting to communicate. This needs a calm atmosphere, and a quiet indoor arena is ideal. Make a blessing out of a curse, by being happy to be in there where you can create an island of calm where learning is likely to happen.

About the Author

Named “One of the 50 most influential horsemen of the Twentieth Century” by The Chronicle of the Horse, Denny Emerson was elected to the USEA Hall of Fame in 2005. He is the only rider to have ever won both a gold medal in eventing and a Tevis Buckle in endurance. He is a graduate of Dartmouth College and author of How Good Riders Get Good, and continues to ride and train from his Tamarack Hill Farm in Vermont and Southern Pines, NC.

December 22, 2017

December 22, 2017