I have unearthed more strange words in the horse world. Though, to be fair, it’s easy to do.

What can be difficult is getting to the root of these words and sorting out how they came to be so common to us, and so foreign to everyone else.

Cavesson

“Yes, hi. I’m in the market for a cavesson noseband and a lunging (or longing, as some prefer)

cavesson please.”

To us, these are two different pieces of equipment. One fits on your bridle and is a plane noseband and the other is more halter-esque with metal rings on the nosepiece in which to attach the lunge line. Even though there are marked differences, they’re essentially the same thing.

The word cavesson is not in my perfect dictionary or on my favourite etymology website. I was under the illusion that this was a common enough word to be found in each. I randomly searched the word online and of course, all kinds of horse-related websites popped up. I guess what I was looking for was, who actually knows what this word means that lives outside of the horse world?

I upgraded my search and entered cavesson meaning, and Dicitionary.com gave me the definition of, “the noseband of a bridle or a halter.” I was pleasantly surprised by this, yet none the wiser as to its origin. Merriam-Webster online dictionary, however, gave the definition of, and I quote, “a noseband made of metal or other stiff material well padded and used on horses especially during breeding or training.”

And while I don’t totally disagree with their meaning, I must admit I was a little shocked to learn they believe these things are made of metal or “other stiff material.”

I feel like the “well-padded” bit was a late addition done in the act of backpedaling. By and large, the cavessons of today are well-padded, but they sure aren’t metal. Merriam-Webster seems to be straddling two different noseband eras here in one unpunctuated sentence.

Nevertheless, they tried.

Out of curiosity and for the love of all horse noses I did a quick search and learned that indeed cavesson nosebands used to be metal. It just seems odd that Merriam-Webster is focusing its attention on a noseband from the 1st-2nd century rather than, I don’t know, the 21st century. I’d even take the 20th century, but I’m not in charge of such things so I will let it go. For now.

Since my normal resources have failed me on this subject I was forced to stick with Merriam-Webster for the etymology portion.

The word cavesson has been around since the 16th century and comes from the Italian cavezzone, which means a halter with a noseband, as halter in Italian is cavezza. I’m not even going to question how a halter works without a noseband. These words go all the way back to Latin and the word capitium, which is of course the opening of a tunic in which to stick your head through. Caput/capit means head and where the word cap comes from, as an FYI.

So, long story short, the cave portion of the word has more to do with the head and nothing whatsoever to do with a cave or a hollowing. This makes sense since a cavesson, no matter which one, fits on our horse’s head.

Surcingle

We turn now to surcingle. I always felt this to be a common word. One that everyone from all walks of life knows and uses liberally. My assumption, as always, was wrong.

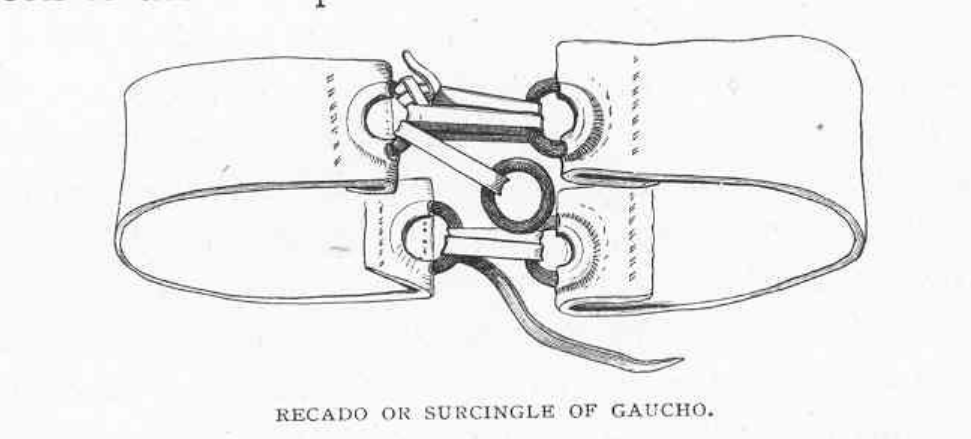

A surcingle is a belt of sorts. It goes around the circumference of our horse where the girth would normally sit. It is commonly used these days for lunging, in lieu of a saddle, or it can be used to keep your horse’s blanket in place.

My dictionary has elected to leave this word out, however, etymonline.com has elected to run with it. Phew.

From the Old French of the late 14th century, today’s word comes from surcengle. Sur meaning over and cengle meaning girdle, which comes from the Latin cingulum which is belt or girth.

That is what I like. A clear and simple explanation as to why a word is, the way it is. Why can’t everything in life be this simple?

I was going to end this post here, but since surcingle was such a cinch, I thought perhaps we should look at that word as well.

Cinch

While I’m here I thought I might briefly touch on the all-important girth.

Girth derives from girdle and is Germanic born rather than Latin. In the early days, it was gjord which is Old Norse and then morphed into gertu before turning into girth and girdle.

Moving on to Cinch.

I find that cinch is used more frequently in the western world than the English, though I do tend to say, “Careful, he tends to be a bit cinchy,” rather than girthy. Not sure why I do that, but I do.

Etymonline.com has once again prevailed. Cinch comes from the Spanish word cincha which means girdle which is just a fancy way of saying girth. And the word cincha goes back to the Latin cingulum, which means this portion of the post has come full circle and I’m quite pleased about that.

November 29, 2022

November 29, 2022