I remember being 16 years old and feeling the tears streaming down my face. I remember walking off the cross country course with my head hanging down and my pelvis tipped forward as waves of tears wracked my body. As we walked past the fields full of horses lining the course at Erie Hunt & Saddle Club, one horse took off running, and with that, my horse flew sideways.

In a tempered rage I picked up the reins and began spurring my horse. I had finally snapped. I had officially lost it.

I was told that in order to test for my C-3 in the United States Pony Club I had to complete a recognized event at training level—on my own horse. Because unlike many of the neighboring pony clubs in the Tristate area, there were no 3* horses sitting around Meadville, PA that I could borrow or lease. No upper level riders were offering their own mounts, so I was stuck with Levi.

Me and Levi at EHSC, 2002.

Levi was an amazing horse. We were competently competing at Second Level in dressage, and up to the Horse 2 level in jumpers (roughly 3’6). And when the fences on XC were solid, he had zero hesitation. But when anything involved water, Levi froze.

So for a solid year we fought. We would go into dressage and throw down a sub 30 score. We would go double clean in stadium. Then we would leave the start box on XC and gallop the first 10 fences out on a beautiful opening stride. But as we’d cruise to the water I would feel his body tense up, followed by a stop, and another stop, and then an outright knock-down drag-out fight. Then we’d walk the fence line back to the trailers, my head hanging low, and have one discussion after the next—with my trainer, my parents, sometimes even with my priest.

I didn’t have the option of leasing another horse to make the move up. I didn’t have the funds to buy a second horse, much less board another. And I refused to sell the horse I owned, and loved.

So I burned out. I stopped competing.

For eight years, I rerouted. I went and worked as a wrangler at a ranch in Wyoming. I hung up my Charles Owen and bought a Stetson. I covered my Crosby and bought a Billy Cook. And for the longest time I just tried to remember why it was I loved this game.

It took years, but I came to the realization that I loved one thing, and one thing only: the horses. Not the shows, not the ribbons. Not the certificates or trophies.

I loved the grooming, the hacking, the tacking up, and the cooling down. The feeling of early morning mist as it brushed my face galloping through the Big Horns on a horse I trusted—and loved. The cadenced rhythm of hooves as they nimbly maneuvered over the rocks and brush. The heavy breathing of a horse who loves his job.

That’s how long it took for me to find my balance and the desire to compete again; to reignite my passion.

Cowgirl up.

I sit here now, at the age of 31, and I watch the next generation go through the same thing.

Only in this modern day and age it appears that the horses aren’t kept and the riders don’t reroute; they simply burn out and become ashes of the fierce competitors and beautiful riders they once were.

Most of these talented kids are on the rat race known as Young Riders, and their horses become byproducts of the race. As a horse seller myself it becomes both a selling point and a fear. We take these young horses and get them going to beginner novice, or maybe novice. We make sure that they are amateur-friendly for a capable teenager in a good program, and then we sell them off into the beautiful unknown. And, for the first few years, it is all rainbows and butterflies; the move ups, the ribbons, the smiles.

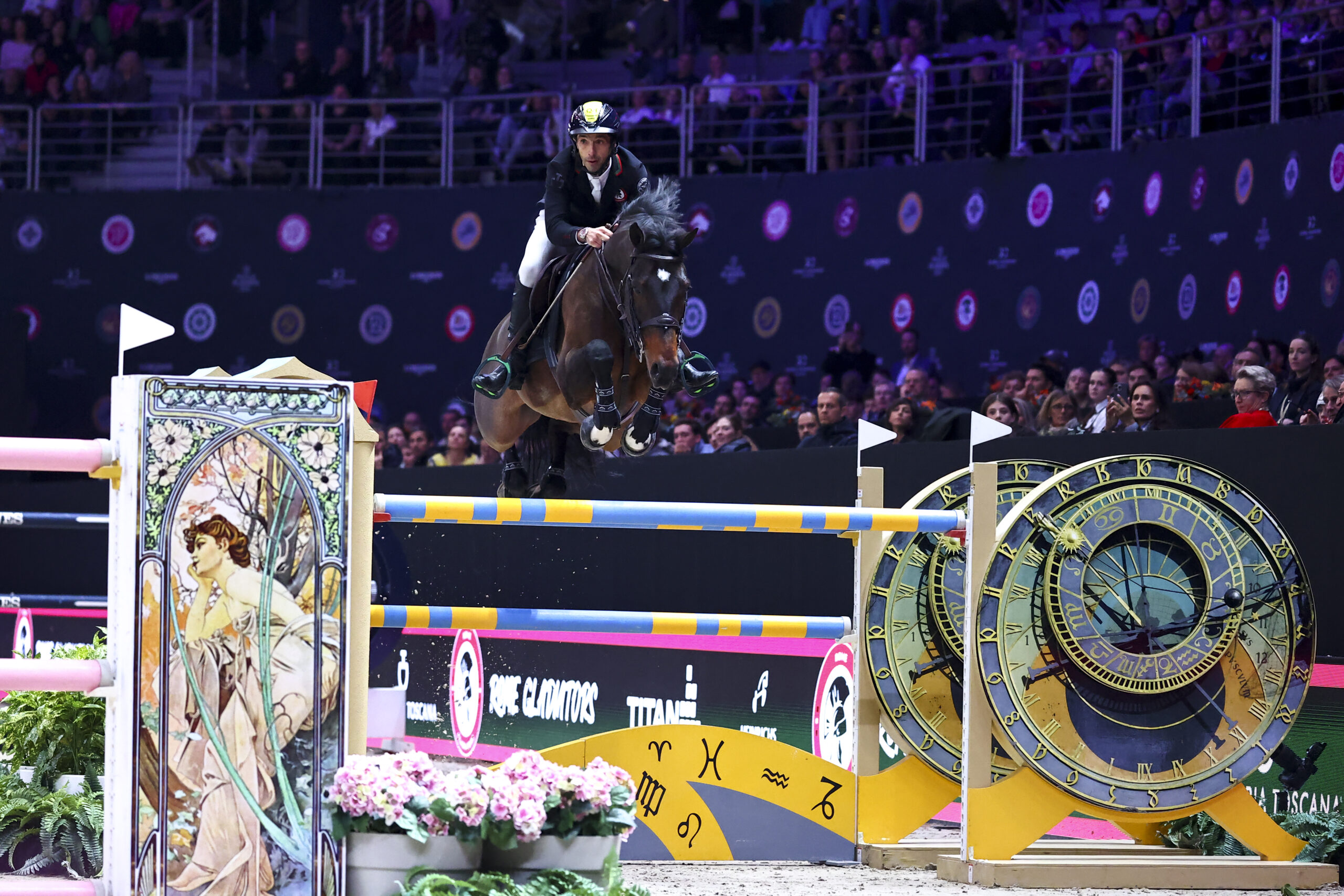

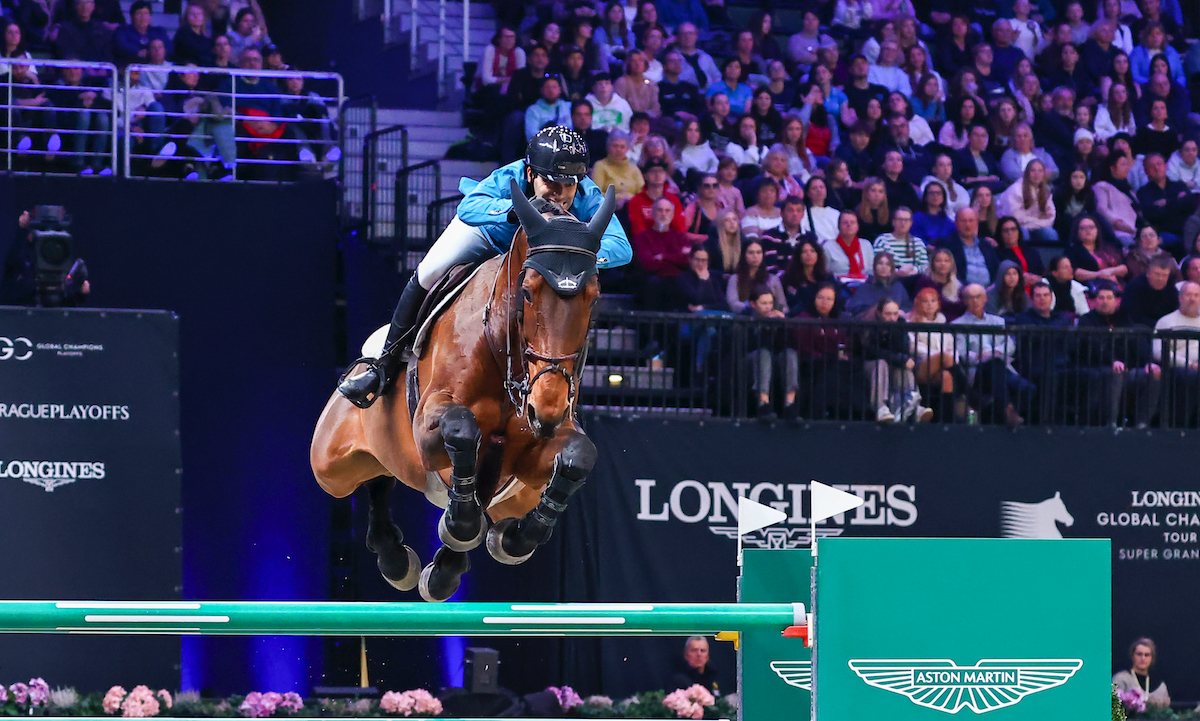

©Alex Carlton

My Facebook feed is full of these teenagers, both boys and girls. They have just purchased their first “real” horse at the age of 13, and for the next couple years, we see nothing but gushing posts and love for their new acquisitions…Ribbons at their first novice—for both horse and rider, and successful shout outs to loved ones and friends…

Then, they get the hunger. They start craving that 1* and they realize their timeline. If they are going novice at 14, then they need to be going training at 15, because they need to be going preliminary at 16 and aiming for that 1* qualifying ride at 17.

The timelines are set, and the rat race begins. This is usually when we stop seeing the happy posts. Instead, we see pictures of iced-down legs and applied bandages. Horses who were happily packing around novice are suddenly shutting down at training level, and instead of moving backwards we see more pushing, and more kicking.

This usually lasts for about one season before we see the horse advertised as for sale, with holes in a record and a distaste for the “upper levels.” The young riders have one of two avenues: they either have the funds and the connections to buy or lease that “been there, done that” horse, or, they quit.

©flickr/australianshepherds

I have seen too many of them quit. I have seen too many of them become remnants of their once vibrant selves. Yet, it doesn’t seem to stop the next wave from doing the same thing.

Then I go watch the competition at Young Riders and think to myself, these aren’t always the best riders. The rat race doesn’t weed out the weak, it weeds out the unlucky. The poor. The small town rider like me who didn’t have access to the older advanced horse. The young girl whose parents thought $5,000 was a LOT to spend on a horse. And the girl who loved her first horse too much to sell him and obtain another.

That’s not to take take away from the riders who do make it. A large portion of them deserve every ounce of that reward and reputation. But not getting there does not make the other riders anything less. It doesn’t make them any weaker and it isn’t a predictor of future success…as long as you don’t let that single failure define you, which is what I have seen happen far too often.

Riders quitting. Horses being tossed to the side. The future members of our sport running away from it instead of embracing it. Young kids who should be enjoying the moments with their horses instead of resenting the failures they are pushing the horses towards. 15 and 16-year-olds who are defining their futures based on a riding competition. Kids who should still be jumping on bareback and going on adventurous trail rides with their barn-mates.

Kids should be having fun, doing kid things.

I was one of them. Granted it wasn’t Young Riders that broke me, it was my own rat race through the level of the United States Pony Club. But I burned out. I faded. And it took a long time for me to find joy in the sport again.

I don’t know the solution.

I don’t want Young Riders to be eliminated, because I think the riders who achieve victory within the program deserve the praise and accolades.

I do believe the ages need to change. I don’t think that at the age of 19 you should suddenly be forced to do a 2* to consider yourself a worthy rider, and I do think that 14 years of age is quite young to be considered a competent enough rider to gallop around a 1* track. Just as Pony Club has increased their age limit, the Young Rider organization needs to as well.

I don’t believe selectors should be able to choose the teams, and I think the politics need to be removed. It should be a points system—an average of the scores obtained at the qualifying events. We have discussed this at length for our Olympic teams, and I think the same needs to be considered for these teams. And, this shouldn’t be considered a ‘make or break’ scenario for this younger generation of our equestrian sport. These kids need to see the bigger picture.

Photo by JJ Sillman

Our sport is one of the few that doesn’t have an age limit. We just witnessed 61-year-old Mark Todd cruise around yet another olympic course, 30 years after his Olympic career began.

We see the entry list at Rolex filled with both USPC ‘A’ graduates and USPC flunk outs. We see Olympians get eliminated and riders who have never been selected to represent our country place. We see Young Rider gold medallists, and others who never made the team.

Looking past Rolex, the Olympics, past the podiums and the pedestals, you have riders like me. Adults who might never run a 4*—hell, who might never run a 1*—but who love this sport just the same. Riders like me who got stuck in the rat race, burned out, and somehow regrouped. Who found their foothold in another destiny, in another avenue.

I might never be a world champion rider, but that doesn’t mean I can’t be a world class horseman. A title that no one can deny you. A skill set that only you, and you alone, can achieve. Because that is the greatest victory to obtain. Not the gold medal. Not the asterisk next to your name.

Pride is great and accolades are awesome, but strength is better. And having the strength to overcome the rat race and still become an avid horsewoman or horseman is the true highest achievement.

About the Author

Carleigh Fedorka is a Ph.D. student at the University of Kentucky’s Gluck Equine Research Center. A Pennsylvania native, she moved to Kentucky after graduating from St. Lawrence University and has worked closely in all aspects of the thoroughbred industry. She spends her free time eventing as well as training, selling and rehoming OTTBs. Read more about her horse life at her blog, A Yankee in Paris.

April 4, 2017

April 4, 2017