Saddle seat riders love a challenge.

They live for exciting experiences like catch-riding a new horse or trying a new discipline, and they pride themselves on their adaptability. But is this adaptability real or simply imagined?

While an adaptable rider can, of course, come from any background, it seems that saddle seat riders may be correct that, as a general rule, they have a propensity toward adaptability, and it may be due to the core strength the discipline requires.

At least, that’s what artist/equestrian Chris Cosma hypothesizes.

In 1996, Cosma created the equestrian fitness tool known as the Home Horse to help keep his sons legged up between riding lessons and horse shows. In using the tool himself, he found that the centrifugal force of the rocking platform upon which Home Horse is built works every muscle an equestrian uses for riding, enhancing a rider’s core, balance and symmetry.

A year ago, Cosma began to market and sell the Home Horse to equestrians of all different disciplines. Upon doing so, he made an interesting observation: though Home Horse could often be challenging for first-time users, those who rode saddle seat consistently were more adept at using it.

“Saddle seat riders, out of riders of all different disciplines, are really the strongest of the group,” said Cosma, who’s equestrian experiences stretched from ponies and project horses to saddle seat show horses, as well as the jumpers and eventers he rode all the way to Olympic trials.

“That’s because they are right at the edge of the motion of the horse. They’re never ahead of it and always in danger of being left behind it, so you have to have a pretty strong core.”

This phenomenon finds its roots in the way saddle seat horses carry themselves and the energy they are asked to expend when performing.

Regardless of discipline, a horse’s center of gravity is the most advanced point of support for its mass. This point lies behind the withers, but varies slightly from horse to horse due to conformation differences. It is also closely tied to the horse’s center of motion, which—unlike the center of gravity—changes as the horse moves depending on the level of collection. Saddle seat horses perform with a high level of collection and, therefore, a center of motion that shifts significantly toward their hindquarters when they move.

Perhaps the most important task of any rider is to stay with the horse’s motion. Since saddle seat is all about upward and forward energy, rather than “following the motion” as riders of many disciplines do, saddle seat riders ride on the furthest edge of the motion for a very specific reason.

As most equestrians know, getting behind the motion can be used as a driving aid. Since saddle seat riders are constantly asking their horses to be as energetic and animated as possible, it makes sense that they would choose to ride almost behind the motion. However, “living on the edge” like this without actually getting left behind requires a high level of fitness.

“Horses don’t always move steadily; they move out from under you, move out to the side, and your ability to not hang onto their mouth and not get left behind is the result of a well-toned, well-muscled, responsive, long core,” Cosma said.

Smith Lilly, World Champion Saddlebred trainer at Mercer Springs Farm in Princeton, West Virginia and author of the book Saddle Seat Horsemanship, agrees.

Though he is one of the leading trainers in the saddle seat industry, Lilly has also ridden some dressage and hunt seat. He believes jockeys have the best balance out of riders in any sport simply because of the high speeds at which they ride. But, he says, the balance of saddle seat riders takes a strong second place.

“I think saddle seat riders have excellent balance because we are riding our horses to peak of their energy,” explained Lilly. “We want them to trot with all of their athletic ability at any given time. We are asking a horse to work at 100 percent of their energy level, and I think most other disciplines don’t do that.”

And with greater energy and animation comes a greater need for fitness.

“It requires a lot of skill to ride a big moving horse without grabbing the reins or calves for balance,” continued Lilly. “As the movement gets progressively bigger you need more core strength, and need more balance.”

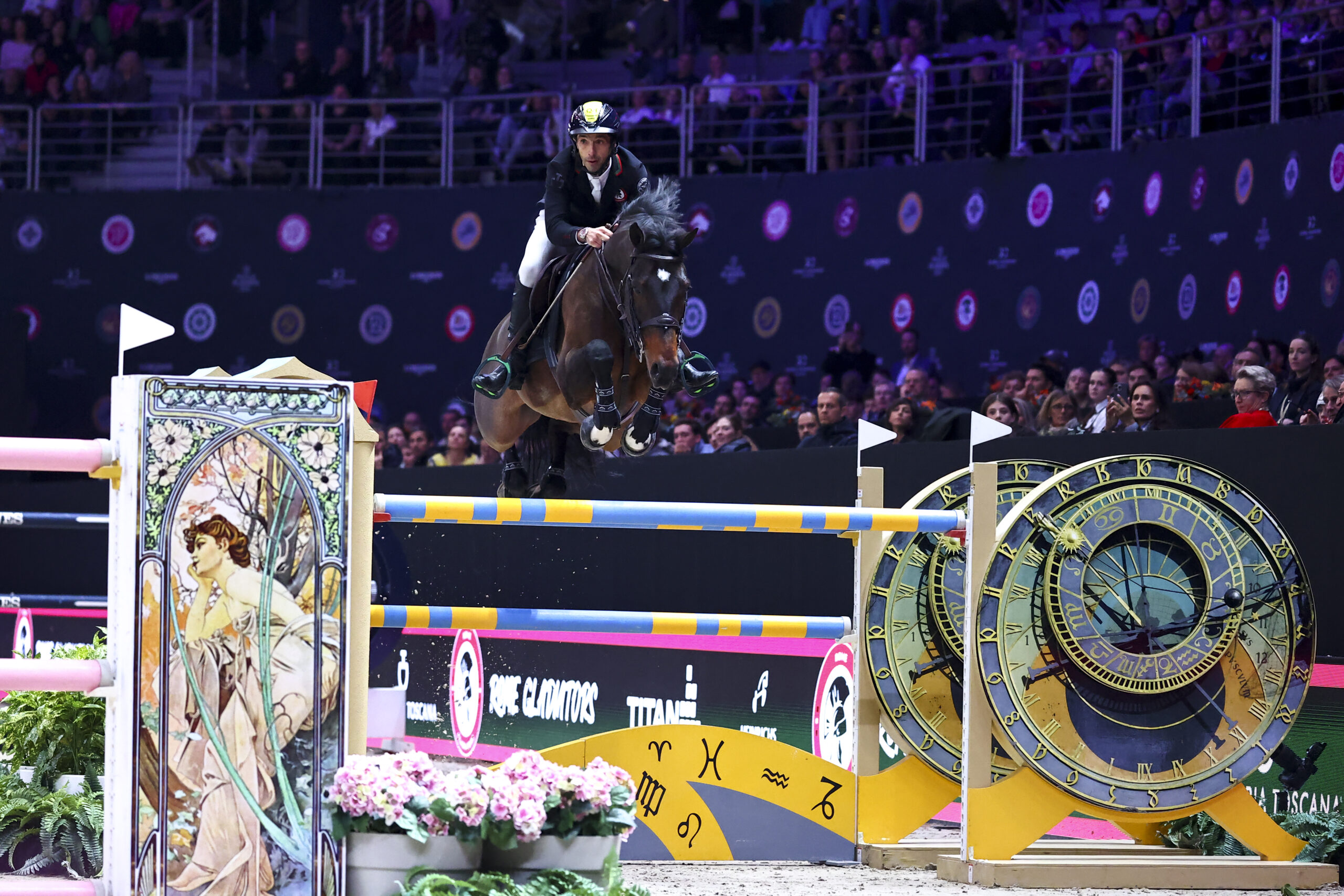

Photo courtesy of the American Saddlebred Horse Association.

Saddle seat riders are asking their horse to trot bigger with each step. That is why Cosma believes the ability to stay over the horse’s center of motion might be more vital in saddle seat than in other English disciplines. But that is not to say that riders of other disciplines can’t master this skill. The best riders are the ones who are able to hop on any horse and stay with it, regardless of discipline.

“That ability is athletic, and it’s trained, and it’s based on one’s core strength, balance and symmetry,” Cosma said. “A good rider that’s toned can hop right on and figure it out and go. That’s the key to good horsemanship, in addition to being able to take care of your horse.”

Lilly said that this ability allows a rider to learn new disciplines faster.

“I think every discipline has its specific skills you need to learn to ride it well, but if you have good balance it’s much easier to learn the skills,” he said.

“If I can stay in the middle of that horse and stay with that horse’s movement, then I’m teachable. Then I can learn whatever skills I need to learn for reining or western pleasure or jumping. If I can’t stay with the horse, then I can’t learn to do much.”

Since saddle seat riders have to learn this skill in order to successfully ride their own horses, they are able to transfer that to other horses as well.

“If you’re used to staying with a big moving horse, it’s easier to stay with whatever else you’re riding,” concludes Lilly.

To a rider with a strong core, that “whatever else” could be a western pleasure horse or a Grand Prix dressage horse, an energetic jumper or even a wooden saddle on a wobbling base like the Home Horse. And maybe that is the real beauty of saddle seat—wherever you want to go in your equestrian journey, it provides skills that can help you get there.

About the Author

Allie Layos is a lifelong equestrian with a passion for the written word, and she likes nothing better than to combine these two interests. While she has ridden multiple disciplines, her first love is saddle seat, and she serves as editor-at-large for the international show horse magazine, Saddle & Bridle. Her work has also been featured in a variety of equine-related books, websites and other publications.

March 30, 2017

March 30, 2017