During the same month Eddie “Shorty” Sweat lay dying of multiple ailments, including cancer and heart disease, Western Horseman magazine released its December 1997 issue with an article commemorating the iconic Secretariat.

In it, the editors selected a photo of one of the horse’s most triumphant moments, the winner’s circle at the Kentucky Derby. There’s Secretariat, himself; gleaming with sweat beneath a blanket of red roses, just moments after the first of three consecutive wins that would earn him the 1973 Triple Crown title for the first time in 25 years. The caption lists the horse’s many connections: his owner, trainer, jockey, and even his owner’s sister. But the black groom standing closest to Secretariat in his white tartan pants with a confident hold of the colt’s lead line is referred to only in passing.

“Unidentified handler,” the caption reads.

History books have always recorded the deeds of great horses, their valiant riders, and benevolent owners. But the stories of grooms are less known.

These are the faithful companions who rise before dawn and leave at dark. Who obsess over leg wraps and clean stalls, notice the smallest change in a horse’s sleep routine, or how and where he eats his hay or leaves manure. They are the men and women trained to identify the slightest heat, change, or swelling in a leg or foot, while their own hands callous over in the summer months, and blister with chilblains in the winter.

The groom, so often, is the first to be forgotten.

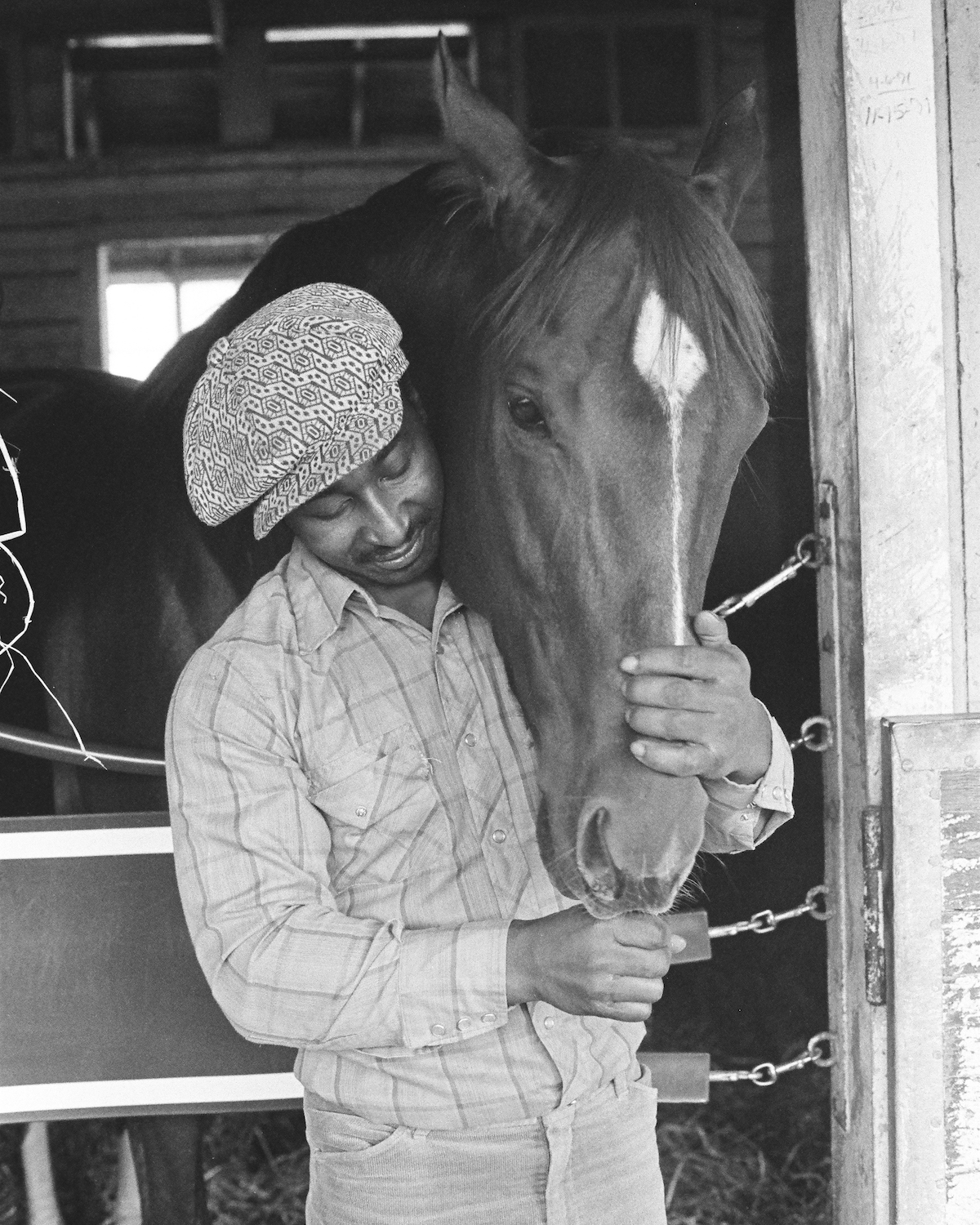

For more than two years, Eddie Sweat was Secretariat’s constant companion. Rarely more than a few feet from the chestnut phenom, the experienced groom did achieve a degree of fame during the mid-1970s, not only for his frequent presence in the winner’s circle, but his clear and fervent dedication to the colt he called “Big Red.” Eddie slept on a cot outside Secretariat’s stall on race days and watched his every workout before fulfilling the daily routine of bathing and cooling out, blanketing, wrapping, and feeding. According to witnesses, Eddie spoke to Secretariat constantly, often in a steady stream of Geechee or Gullah, a Southern Creole language spoken by his family.

“It was a relationship on a much different scale than most people, even those people that own horses, or have horses living on their property,” says author Lawrence Scanlan, who set out to capture the unique bond between the Thoroughbred and his groom in his 2006 non-fiction book, The Horse God Built: The Untold Story of Secretariat, the World’s Greatest Racehorse.

“Eddie’s relationship with Secretariat was [intimate] and much more around-the-clock.”

The son of poor tenant farmers from a family of nine children, Sweat grew up near Holly Hill, South Carolina during the 1940s—prime time for the oppressive segregationist laws of the Jim Crow-era South. It was there that he began to work for French Canadian trainer Lucien Laurin’s Holly Hill Farm, first as an exercise rider, then graduating to groom after he grew too heavy to ride.

From their earliest days together in South Carolina, Laurin took Eddie under his wing, including when he came out of retirement, first to train the Derby-winning racehorse Riva Ridge at Peggy Chenery’s Meadow Stable in Virginia; then Secretariat in the 1970s. It was a leg up Eddie never forgot, and the groom continued to work for Laurin and then his son Roger Laurin for the majority of his life.

“Eddie learned a great deal by working with [Lucien] and around a bunch of other people. But he came to the task with certain qualities,” says Scanlan, who wrote that Eddie’s father David was part Cherokee and good with horses, teaching him how to gather herbs in the forest for home-made poultices.

“[Eddie] had some kind of natural and maybe acquired ability to relate to the horses and understand what they needed. He was a very gentle, kind man, but he would brook no nonsense.”

This was especially important when it came to working with the large, imposing, and notoriously headstrong Secretariat.

“The horse was very difficult. He was fractious. He would rear,” Scanlan says. “Eddie had this kind of laid back, sing-song chatter that he emitted all the time, and the horse just loved him.”

In fact, the unique set of circumstances that groom and horse faced down together only strengthened their partnership. From quiet moments on the backstretch to the incessant, flashing camera bulbs of the winner’s circle, Eddie, Scanlan believes, became a kind of human security blanket for his charge.

“There’s this photograph in the book of Secretariat on the plane going to [Claiborne] Farm, where he will live out his days [at stud]. He’s unnerved by the sounds of the engine of the airplane, so [biographer and photographer] Raymond Woolfe got a shot of Secretariat’s teeth, and he’s got a hold of Eddie’s jacket,” Scanlan recalls.

“It’s like a toddler afraid of something, going to a sibling or a mother or father [for comfort]. It just captures the bond between them.”

****

Few grooms are fortunate enough to have one famous horse in a lifetime; in Riva Ridge and Secretariat, Eddie Sweat groomed two.

During the peak of the latter’s Triple Crown fame, Eddie made television appearances, graced the covers of Ebony and Jet magazines, and was later immortalized in Ed Bogucki’s bronze Secretariat statue at the Kentucky Horse Park in Lexington—a work of art that partly inspired Scanlan’s book.

And yet, what money and accolades Eddie acquired quickly came and went. According to his friends and family, the groom was unfailingly generous, known not only for loaning money to those in need, but for using his influence to help secure good-paying racetrack jobs for relatives. But Eddie never forgot the role imposed on him by his era, race, and station.

“He grew up a black man at a time when hired help didn’t look [their employers] in the eye,” Scanlan says. “So, when [Owner] Penny Chenery would be talking to him, he was all, ‘Oh, yes, ma’am. No, ma’am.’ He was [even] offered work as a trainer later in life, and I guess he didn’t have the confidence. [Eddie] just said, ‘I’m a groom. That’s what I set out to be, and [that’s what] I will continue to be.’”

It’s one of many ways that The Horse God Built doesn’t shy away from the harsher realities of life on the track. In it, Scanlan includes a line from Anthony J. Schefstad’s 1995 University of Maryland Ph.D. thesis, in which the writer equates a groom’s life on the backstretch to “the last operating serfdoms in the United States.”

It’s a truth that resonates in Eddie’s own story: the long hours and sleepless nights for limited wages, the propensity for hard living that accompanies life in the shed row, the extensive time on the road away from his wife Linda and their children in New York.

While researching the book, Scanlan spoke with Lucien Laurin’s notoriously tight-lipped barn foreman Ted McClain. The author recalls that it was the mention of Eddie’s name—and Eddie’s name only—that eventually convinced McClain to agree to be interviewed, and that he spoke of the groom with something close to reverence.

“Eddie was a prince,” were McClain’s actual words. And yet, the last years of Eddie Sweat’s life were far closer to that of a medieval villein than a monarch.

Despite being the man closest to a six-million-dollar racehorse, Sweat was impoverished when he passed away in 1998 in a hospital not far from Belmont Park in New York, where Secretariat ran (arguably) his most astounding race. His wife Linda, a kindergarten teacher, had been covering Eddie’s medical expenses on her insurance; the Jockey Club paid for part of the casket, and his former employer, Roger Laurin, quietly covered expenses for Eddie’s family to travel down to South Carolina for his funeral. As reported in The Horse God Built, no “white folks of stature” from Eddie’s glory days with Secretariat—not a single owner or trainer—attended his services.

To be sure, there are two sides to every story. But what seems particularly unjust to Scanlan is how little it would have taken for Secretariat’s connections to set things right.

“Eddie should have received, I think, a much better, much greater share of the great wealth that Secretariat accrued in his time as a racehorse and as a stud,” he says.

“The great biographer of [Secretariat: The Making of a Champion] William Nack told me that all it would have taken from Secretariat was one cover. In other words, Secretariat mates with another horse, [and that breeding] becomes a horse and is worth a small fortune, and you give that horse to Eddie [to either train or to sell], and then Eddie is looked after.”

If that’s the case, there were plenty of foals to go around. Though some racing historians have criticized Secretariat’s breeding career due to his inability to sire either progeny to rival his legacy, or a leading stallion to fill his shoes, Big Red’s daughters were renowned as broodmares.

In addition, while covering many of the finest mares of his day, the chestnut stallion produced a total of 663 named foals. More than half of those went on to be winners, including nearly 60 stakes winners. In total, Secretariat’s offspring won some $29 million on tracks across North America.

****

There is another, more subdued photo by Raymond Woolfe that graces the pages of The Horse God Built. It’s a picture taken the day that Eddie Sweat and Secretariat made their final journey together to the breeding shed at Claiborne Farm, when the Thoroughbred was officially retired as a racehorse, and the groom officially gave up his charge.

“[Secretariat] has been put in his stall, and Eddie has said his goodbyes, and you see a little suitcase beside him,” Scanlan says. “And you can see [Eddie] has brought up his [left] hand to wipe away a tear.”

According to Woolfe, who Scanlan interviewed for the book, Eddie was circumspect on that day when the photographer asked him what was wrong.

“I’ve just got a cold,” was the reply.

If the groom harbored any regrets about that day, or any of the days before or after, he also kept those close to his chest. But Scanlan hints there may have been some.

Just years before his death, Eddie gave an interview to Daily Racing Form in which he said he still had hopes of “coming up with another big horse” to groom. Alas, Eddie, then in his 50s, was already struggling both physically and financially, and the last, ‘big horse’ never came. What’s more, some of Eddie’s friends suggest that the death of his old friend Secretariat in the fall of 1989 from laminitis also took a toll on the groom’s health and wellbeing. At least one reports Eddie expressed discontentment about his treatment by former employers during his dying days.

One clear wish Eddie Sweat did have, according to his friend and fellow track groom David Walker? To become the first groom inducted into the Horse Racing Hall of Fame—an honor currently reserved only for horses, jockeys, trainers, and the like. At least, in that, there may still be some hope: according to a Care2 petition created for Sweat, only a handful of names are still needed to meet the petition’s goal of 1,000 signatures (you can sign yourself here).

Nearly a quarter century after Eddie Sweat’s passing, it’s something horse racing fans everywhere can still do to honor him. And a small way, perhaps, to pay tribute to one of so many ‘unidentified handlers’ that, by birth or circumstance, history has repeatedly pushed into the shadows.

“[Eddie] was all about the horses, and I think, on the one hand, he understood that [very few people] actually enjoyed a connection [with them] the way that he did,” Scanlan reflects. “But I also think there were other parts of his life that were [fairly] miserable and sad.

“I think Eddie paid quite a price for that bond.”

Protect Your Passion

AIG is proud to bring stories of passion, provenance and preservation, like Eddie Sweat’s story above, to life.

At AIG, we share your passions … and we’ll help you protect them. Count on AIG’s world-class underwriting, risk management expertise, financial strength, and white-glove claim service to help mitigate the complex risks of your distinctive lifestyle.

Insurance is underwritten by the member companies of AIG.

March 23, 2022

March 23, 2022