Her father is Canada’s most decorated equestrian athlete. Her mother, a highly respected horsewoman. Amy Millar shares what it was like growing up in the Millar household, as told to Carley Sparks.

Growing up Millar you go on a lot of road trips.

Photo courtesy of the Grajewski family collection

Like a lot, a lot. In my first month alive I was at a horse show. My dad, a stockbroker by trade, had recently gotten a job riding horses, which was not all that common at the time. Since my mom was a nurse and I was the second child, she sent him to Florida to do his job and had me at the hospital in Ottawa where she worked on Valentines’ Day 1977.

People still come up to me and say “I remember the day you were born!” because they were riding around Ocala horse show when the announcement was made over the loudspeaker: “Congratulations, Ian! Amy Lynn Christine Millar has been born.”

A few weeks later my tough-as-nails mother packed my brother and I up in a truck and drove us down to Ocala to be with my dad for the rest of the Florida circuit. Now that I have a five-year-old of my own, I find it truly remarkable that she would drive across the country with two small children. I have yet to pack my daughter Lily in a car for 24 hours. It seems like a terrible idea.

There were many, many more road trips after that. I’ve probably spent more time at a horse show than not at a horse show if I counted up all my days on this earth.

Growing up Millar we had a lot of freedom.

©Andy Rose

Today, the horse show kids all have nannies and people watching them full time. I spent most of my childhood living out of a camper. Jonathon and I had bunk beds in the back. My parents had a bedroom and we all shared a bathroom. It was one big happy circus family, traveling show to show.

Horse shows were much smaller then than they are now. Everybody had their camper set up and their little play patch out front, cages for the dogs. The kids played together all day. If we wandered off, well, everybody knew that we were Ian and Lynn’s kids and that was the Ward’s kid. They’d just send us back.

It was a pretty awesome way to grow up—riding ponies, building forts, and playing outside all day in the sun. And watching some show jumping, which is probably the least of what I remember. There was way more playing and driving four-wheelers and climbing trees than riding ponies and the rest of it.

Growing up Millar you look after your own pony.

©Jayne Huddleston

There was never any pressure from my parents for Jonathon and I to ride. We could ride if we wanted to, or not. But if we did, then we had to look after the horses ourselves and help out in the barn.

My first pony was a naughty little mare named Cindy. We used to keep the hay between the arena and the barn. I could get this pony trotting away from the barn but just barely. I’d kick and kick. Then we’d turn toward the barn and she would just run straight to the hay pile. I’d cry and someone would come get the pony’s head out of the hay. And we’d start all over.

When we started riding in the jumping field, the same thing would happen. We’d get all the way to the field and she would just run back to the barn.

After Cindy, I got my first show pony, Belvore Starwort. Tommy Gayford had given her to my dad. It was a pony the Gayford kids had ridden. One Sunday night coming back from a horse show, my parents surprised me with her. I remember my mom waking me up at 10 p.m. and taking me out to the barn. They opened the door to the horse truck, it was already filled with horses, and there was this small pony with a cute furry little head standing in the aisle between four horses.

Growing up Millar you learn early on that life is not fair.

I can’t say I was terribly successful in my pony years. I did it mostly just for fun on ponies people would give us. For my last year in the Large Pony division, my parents leased a fancy pony from my trainer, Barb Mitchell. Her name was Nikita Korsay. She was afraid of tractors, so anytime a tractor drove by I’d fall off in the warm up ring. But other than that she was a really good show pony.

That year, I qualified for the Royal first time ever. This pony won a lot, so I had gotten used to winning at that point. The first day, I thought I did really well. Everybody was like, “You were great!” Then I got called back sixth and reserve. Of course, that ended in tears—“It’s not fair! WHHHHY?!”

My mom said, “Life is not fair. Get used to it. All you can do is come out tomorrow and ride even better than you did today and make your pony go even better than you did today. If you do that, then no one will be able to ignore you.”

I came back the next day and did what she said. We won the two over fences classes and the hack and ended up champion. I’ve never forgotten that lesson. It still applies to what I do. Whether you’re riding hunters or trying to get a spot on the Canadian team, you don’t involve yourself in the politics of the situation. You just lay down trips and be better than everyone else and then no one can ignore you.

[Editor’s note: Amy rode her up-and-coming Grand Prix horse, Heros, in his first team event in the Ocala FEI Furusiyya Nations Cup in February 2016. She was the top-placed Canadian rider.]

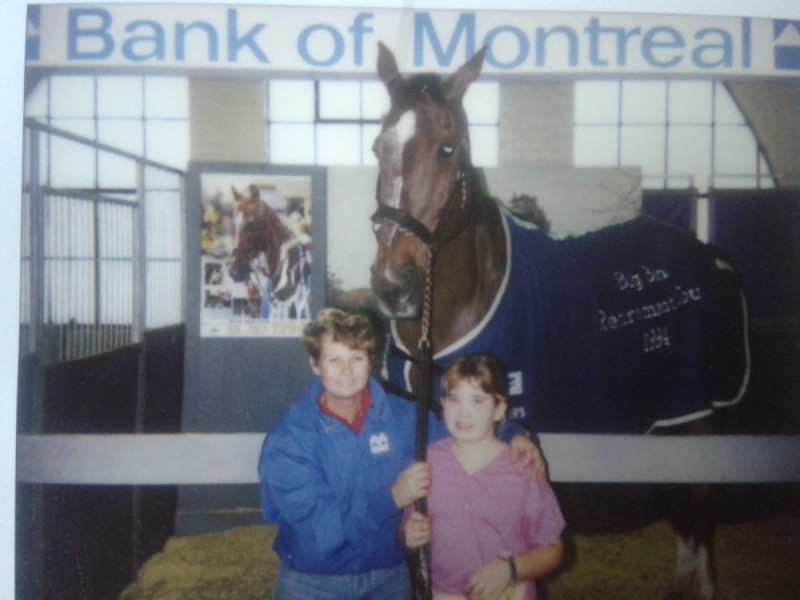

Growing up Millar I didn’t know my dad was famous until the Big Ben retirement tour.

©Kelly Bennett

I was 16. We were at the London horse show and people were taking Polaroid pictures beside Big Ben. Sandy, Ben’s groom, would stand there holding him for however long the line up was. Well, the line was so long, the entire town ran out of Polaroid film!

I had no idea before that. We lived in Perth, population six thousand. Everybody at school treated me like everyone else. I credit my parents for that, too. My dad was certainly very successful at the time, but they never acted like he was something special. When people asked what he did for a living, he’d say, “We’re farmers.”

Growing up Millar the family always come first.

©Jayne Huddleston

When I realized that my dad was famous I began to notice that sometimes people treated me differently as a result. Some people treated me better. Some people treated me worse. Sometimes if I was out at night, people would encourage me to do something stupid and then tell my parents the next day. I was a real Pollyanna. I was always speaking before I thought and doing whatever I felt like. There were plenty of errors to be reported to my parents.

But every time someone came to them and said, “I saw your daughter do this or that”, my parents would defend me. My dad would say, “Amy jumped great in the Grand Prix. Sometimes you need to blow off a little steam.” Then he’d come to me privately and give it to me proper.

People wanted to see us divided. They wanted to get a reaction. The best thing we could do is stand united, but not miss the lesson either. It was never okay, that’s for sure.

It was the same for my parents. My mom was fiercely protective of my dad. If she heard anyone talking badly about him, look out! Even if she agreed. She might say the same thing behind closed doors. But in public, it was always family first and we had to protect each other. It was us against the world.

When my mom got sick, it was our turn to protect her. We did everything we could for her.

Growing up Millar you learn total dedication to horses.

Back in the day

When I got to the age where I was more involved in school and felt more connected to my friends, I went through a rebellious phase. All I ever saw from my parents was this total dedication to horses. Everything in their life was horses. They talked about horses at dinner. They worked in the barn all day. They were so passionate about it.

As I started to grow up and make choices for myself, I wasn’t sure I wanted to make that kind of commitment. Because it’s not just a job, it’s a lifestyle. You eat, breathe, sleep horses. And if that’s not the way you are, you shouldn’t be doing it.

I wasn’t sure that I wanted that life. My mom always made it a priority that I got to do all the different things I wanted to do. I played basketball. I played volleyball. I wanted to be a lawyer. I wanted to be a philosopher. I wanted to be all kinds of different things.

Growing up Millar I felt like a lot of things just fell in my lap.

After high school, I took a year off before I went to University to try this riding thing full time. I graduated half a year early, so I spent the winter in California and then the whole year working for the family business. I had a wonderful Grand Prix horse named Zagal. We won a six bar high jumping competition in Indio that year.

©Jason McQueen

At that age, things came really easy to me. I think it’s probably true for a lot of my life. School was easy for me. Making friends was easy for me because my parents dragged me all over the world and I spent most of my time meeting new people. Riding was easy. I had the best trainers and the right body type.

I know I took a lot for granted back then. And I felt a little bit guilty that everything came so easy for me. Whether it was falling in my lap, or I felt it was falling in my lap, I didn’t have to want to win as much as I do now to be successful. I sort of rode by the seat of my pants all the time and was pretty happy about it. You can get yourself into messes that way, you can get yourself hurt.

Adversity definitely forces you to grow up. I’ve experienced some of that between university and now, losing my mom in particular. It makes you appreciate life and everything you have. And it makes it easier to define what it is you want and build a plan. Since I’ve had my daughter, I try to focus on what it is I want to accomplish in my riding and make a plan to do it. It’s much more rewarding and I’ve learned to really appreciate the successes I have now.

Growing up Millar you put your money where your mouth is.

That gap year made me realize that if I didn’t get a degree of some sort, then I was committing to running our family barn for the rest of my life. I wasn’t ready to do it and I wanted a backup plan, so I decided to go to Ryerson University. I wanted to take Philosophy. My dad wasn’t having any of it.

I hadn’t been the most studious student in high school. I think my parents suspected that I was going to university more to have fun than to study. They said if I wanted to go I needed to a) take something that was going to get me a job and b) pay for half of it myself. They felt I’d be more responsible about it that way. They were entirely correct. It’s a lot easier to spend someone else’s money than your own.

I ended up earning a degree in business. By the time school was done, I knew without a doubt that I wanted a career in show jumping. I worked for a few different show stables in Canada and the United States before I came back to the family business in Perth.

Growing up Millar the Canadian team is always the top priority.

Amy and Jon for Team Canada

These days I’m focused on building my international career. My dad has always been a Canadian team rider. You could have a perfectly happy career in this sport and not ride for your country. The Captain instilled in Jonathon and I that it’s a privilege, an honor, and a goal to be considered for the team.

If you make it, that becomes your top priority. It doesn’t matter if you didn’t get along with one of the other riders at some point in your past. The minute you get named to the team, you forget all the other history. You hang out together. You work together. You attempt to create synergy. And you prioritize the Nations Cup over any other class. There could be life-altering money to be won on Sunday. Friday is the day that you are there for.

With the exception of when we had In Style and Hickstead, Canada has always been a bit of an underdog in international show jumping. We’ve always had less money to spend on horses. We’ve had fewer riders to choose from. We’ve had less training than the American and European teams. So the Canadians had to use everything they could and pool their resources. Statistically, there were so many times the Canadians were never supposed to win. And they would. They’d come together as a team and they’d win.

As my career advances, I want to be in regular rotation on the Canadian team. It’s difficult to come by these fantastic animals. It’s difficult to come by investors who would like to help you buy these animals. It’s a very competitive market. But growing up Millar, “hard” is just a reason to dig deeper.

March 15, 2016

March 15, 2016